“The Sense and Weight of a Haunting” By Joey Chin

About Sichong Xie’s “Do Donkeys Know Politics, Scaffold Series I”

What is the weight of a haunting? US-based Chinese artist, Sichong Xie’s multi-media multi-channel installation Do Donkeys Know Politics, Scaffold Series I made me ponder on that question. Is it empty and ghostly diaphanous? Or heavy in its occupation? Is a haunting based on a traumatic event in the past, trailing from a family’s history and permeating into the present, light or heavy?

Do Donkeys Know Politics, Scaffold Series I is grounded in an incident in the artist’s family, arising from the drawing of a donkey illustrated in the 1950s by the artist’s grandfather, an architect. Deemed as a political caricature, the authorities exiled the artist's grandfather to a labor camp following the publication of the drawing that was considered critical of the government.

Based on this event from more than 60 years ago and transposing its way into Xie’s art today, Do Donkeys Know Politics, Scaffold Series I is made of two key parts. It consists of handmade industrial building scaffolding accompanied by drawings on bed sheets. These drawings on bed sheets are remained washing marks from Xie’s other work, a durational performance/site-specific installation, When the peaks of our washing sound come together, my tree house will have a roof where performers came together to wash and vigorously scrub the drawings off the bed sheets, before thoroughly rinsing, wringing and hanging them out to dry. Despite these laborious efforts, the marks remained.

In the installation, I glean that a haunting alternates between being heavy and light, in materiality or emotion, through the hard and the soft in scaffolding and pieces of drawings on bed sheet laid or draped across; the fabric itself being carefully drawn on before undergoing determined and strenuous attempts to be eradicated through a battalion of strong hands, abrasive laundry scrubs and detergent; reality and possibility through the artist’s determined hand to reify on paper the invisible: time, age and memories of her grandmother’s.

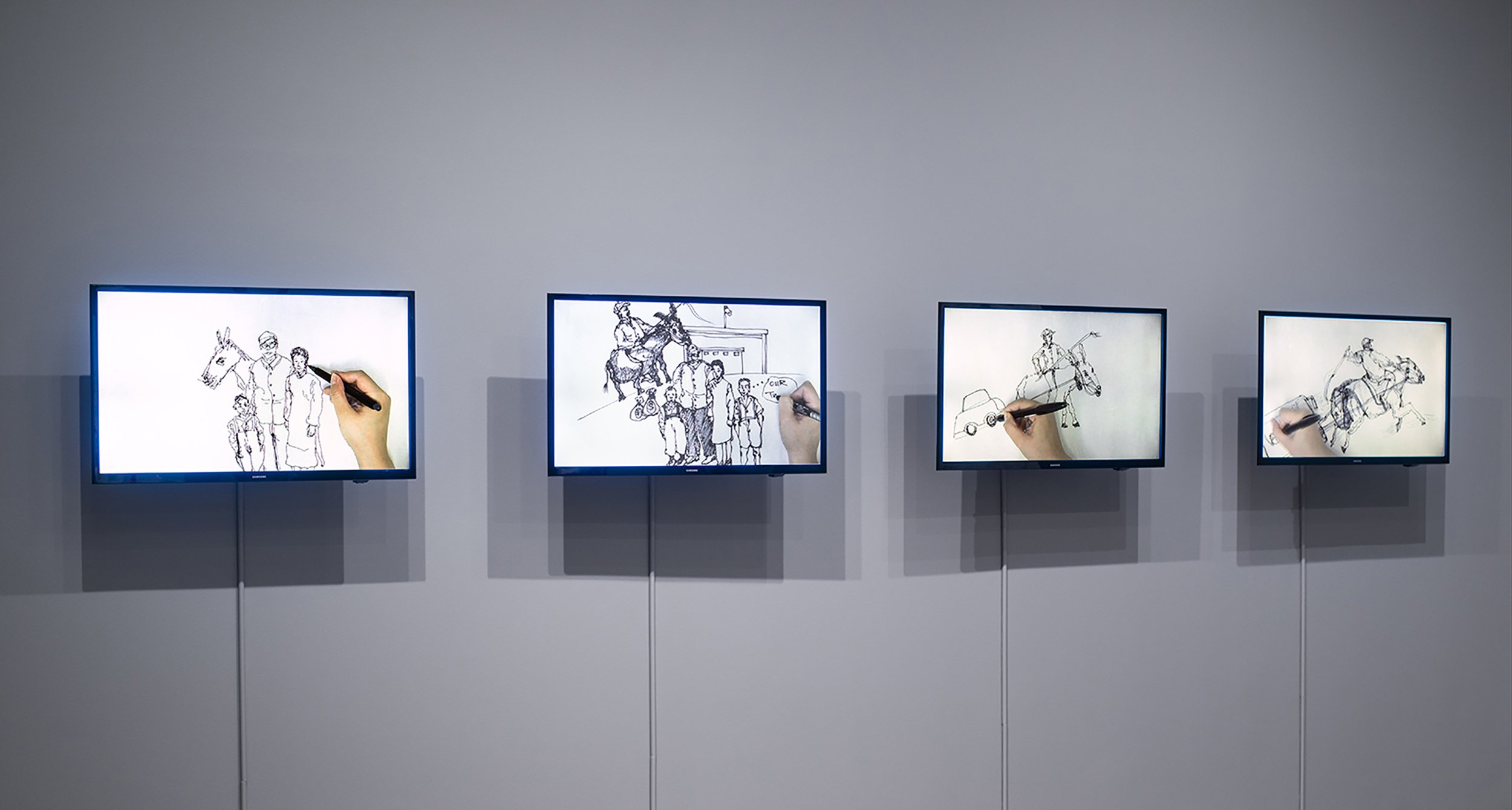

The other part, a video component shows the artist’s hand sketching different versions of the erring donkey caricature according to the instructions and impressions of her grandmother. Each sketch is progressively changed because of her grandmother’s shifting memories of the original work. In each video, the artist voices her grandmother’s critique. From the first iteration to the last, there is a vast difference.

The first video starts off with a sketch of a presumably corrupt governor, a donkey with money bags slung across its back and the backdrop of a government building. By the last video, the unsavory governor is depicted as armed with a sword on a running donkey, and his family in a bus with their belongings stacked on top of it, all being dragged by the donkey. For me, a sense of tragicomic and an absurd disbelief suspends itself between the cartoon and its ultimate repercussions for Xie’s family.

In the videos, Xie shares her grandmother’s corrections with the viewer: “She told me the donkey was not the main character in the illustration,” “My grandmother told me that she remembered wrong”, “She corrected me and told me there should be a bus next to the donkey”, “She told me that the donkey was actually running in the original cartoon”. These discrepancies could arise from memories that naturally fade or alter with time. After all, numerous decades had gone by. In a correspondence with the artist, she had wondered if her grandmother’s continuous changing instructions could be an attempt to actually protect her, the granddaughter.

As with hauntings, there is a sense of misplacement, manifesting in what is either localized and grounded like Xie’s hand, or uncertain and drifting like the grandmother’s recollection. Bordering storytelling and reportage, I sense the intricate intersection of self and another, of being and non-being. The grandmother’s voice is never heard in the video installation, but it is her instructions that dictate the outcome. In Xie’s attempts to grasp the errant donkey according to her grandmother’s descriptions, automatic writing comes to my mind, where the writer is guided not by her own volition, by the summoning of spirits or the initiation of the unconscious.

What remains of a recollection if memory is a palimpsest and patterns of absence and disappearance? Ultimately, the self is momentarily removed and what takes over are externalities: trauma, memory and family history.

If I contemplate the event and the installation as a manifestation of a haunting, then I also consider shamanism, the old discipline transposed into modern practice as a way of facilitating artmaking, with the primary function of serving as a conduit to navigate and make sense of a disruption and disorder: the very incident leading to the grandfather’s exile.

To succeed in the process, it is the actor, facilitator or shaman who must first traverse the axis before returning to the starting point, sometimes repeatedly, with answers or visions whilst negotiating and maintaining control, mediating the needs of different realms to fulfill a purpose to an individual or a people not served or neglected by others.

I see Do Donkeys Know Politics, Scaffold Series I as a way of bridging viewers and audience to another personal and political history, just as shamanism acts as a bridge between worlds, specifically, the world of exile and separation - an incident that is not an isolated one for various parts throughout world history. It is not unlike attempts to bring closer or make contact as a result of segregation.

In Do Donkeys Know Politics, Scaffold Series I, I extend shamanism to artmaking for its relationship-based outcome, in making changes through the invisible realms of trauma to today’s concrete reality, and sometimes, with the use of symbolic objects. The visually compelling feature anchored in Do Donkeys Know Politics, Scaffold Series I is the construction scaffolding, a part that is also mounted the high on a wall. Paying tribute to her grandfather’s profession as an architect, I imagine that it establishes the interim, the nomadic and the shifting, bridging alternate states, a way of facilitating and striving to communicate what is elusive and out of grasp.

Towards the last part of her video, Xie shares with the viewer that she is still waiting for her grandmother’s response. At the very start, I had wondered if she eventually succeeded in replicating the donkey cartoon, if her grandmother was able to summon a memory that was stable and unwavering. Afterall, there was a keen sense of rising action that keeps the viewer wondering.

In writing this now, I see it did not really matter if there was any veracity in the recollections and outcome. Scaffoldings, after all, are primarily support materials for access points to heights, a visual metaphor for the grandmother’s memory which served as a platform for Xie’s art to emerge from.

In Do Donkeys Know Politics, Scaffold Series I, Xie has traversed geographically with the weight of her grandparents’ stories, navigating the heft of history to the emptiness and gaps of memories. In that sense, a haunting is both light and heavy, in wondering whether to hold on and let go, before deciding to make its own haunting a home in the installation.

——————————————

All images courtesy of the artist.

1- When the peaks of our washing sound come together, my tree house will have a roof (2018), Durational Performance/Site-Specific Installation, Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, Courtesy of the Artist.

2 to 4 - Do Donkeys Know Politics, Scaffold Series I (2020), Multi-Media Multi-Channel Installation, USC Pacific Asia Museum, Courtesy of the Artist.

Sichong Xie Sichong Xie is a multidisciplinary artist currently lives and works in Los Angeles, CA. Her practice combines movement and material in body-based sculptural forms, including masks, costumes, and other objects. By placing traditional sculptural forms within new sites, materials, and social constructs, she investigates these forms and movements within global communities to re-consider and re-envision shared spaces and performative practices. She raises questions about identity, politics, cross-culturalism, and the surreal characteristics of her body in the ever-changing environment.

Xie received her MFA from the California Institute of the Arts, CA. She is the recipient of the 2021 Marciano Art Foundation Artadia Award. Her most recent installation, Memory Structure, Scaffold Series, at the Wende Museum in Los Angeles, features objects and arrangements emblematic of memory and temporality: bamboo scaffolding, embroidery on industrial mesh, and a set of laser-engraved drawings that will fade from continual exposure to light, through which she reimagines architectural drawings created by her grandfather in the late 1950s and early 1960s. This installation brings the materiality of the natural bamboo into direct conversation with the mass-produced nature of the scaffold and its role in development. She was a fellow artist at MacDowell Colony, The Studios at MASS MoCA, Yaddo, The Watermill Center, the Fine Arts Work Center, the Vermont Studio Center, and the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture. In 2017, Xie was chosen to participate at the Hauser & Wirth Somerset Exchange residency in Bath, U.K., where she created a four-hour durational performance/installation, "Walking With The Disappeared."