“Bureaucracies from Below” Isis Yépez on Eliza Evans

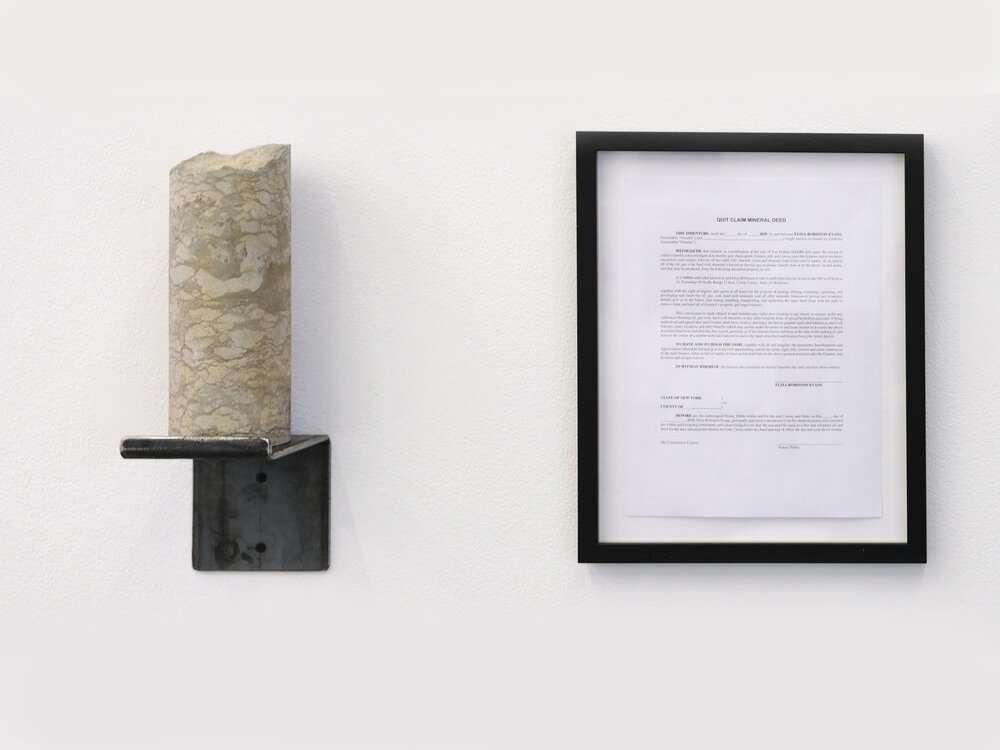

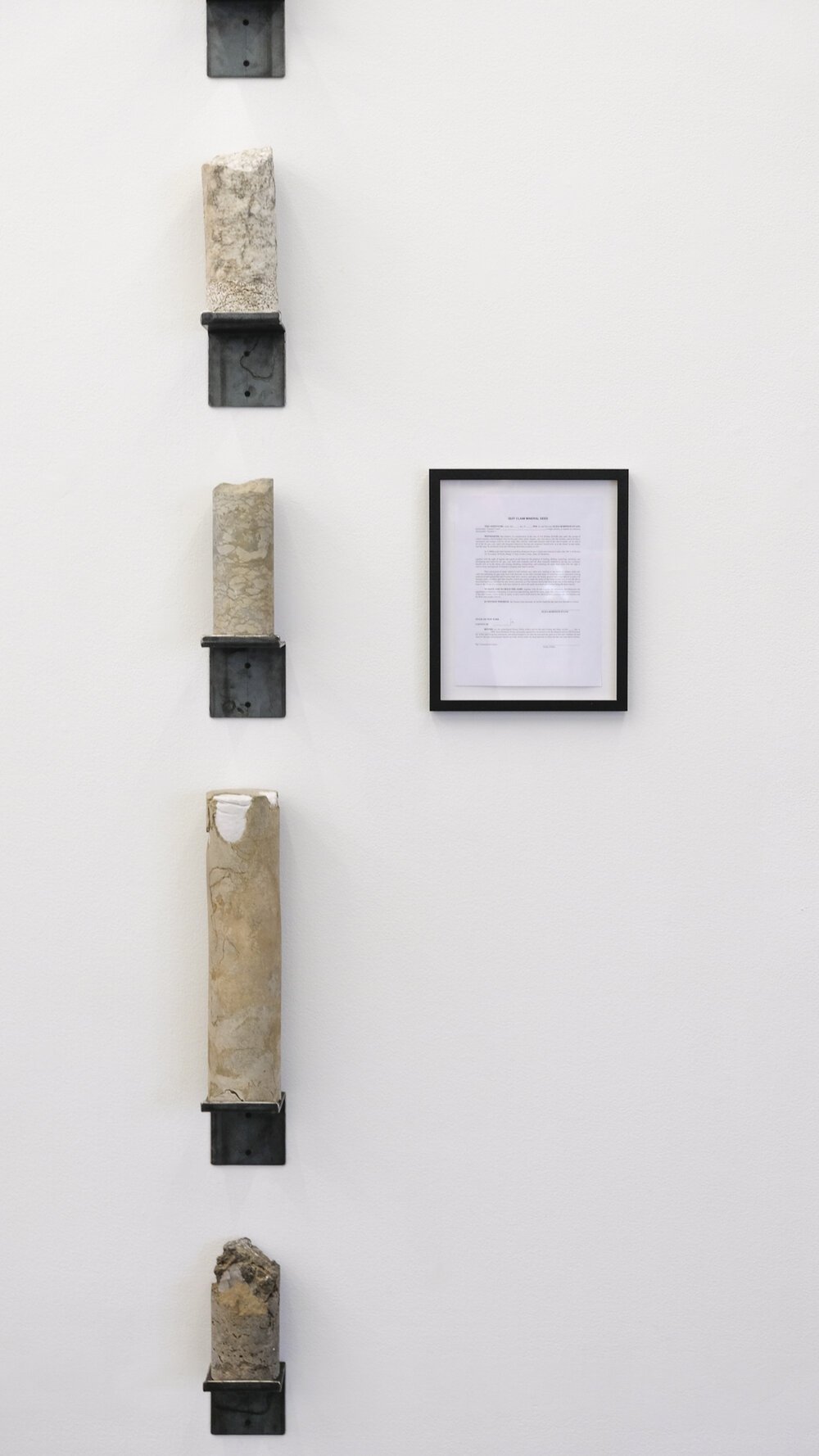

The installation All the Way to Hell by U.S. artist and researcher Eliza Evans consists of a series of well cores from the Permian Basin, the most active oil and gas field in the United States, and a framed mineral deed. Evans relates these artifacts, revealing the roadmap to fracking.

The Mexican geologist Luis Rodriguez states that cores serve as exploration tools; oil and gas companies use them to justify land exploitation. The Mexican volcanologist and physicist, Elizabeth Castañeda, speaks of how, in geology, cores are called witnesses; voices of the geological past: "you can hold them in your hands, access the memory of the Earth, and it tells you what has happened, in its own words." From the Muscogee Nation, the poet Joy Harjo writes: "The Land is a being that remembers everything" (Harjo: 2015), a living archive of the land.

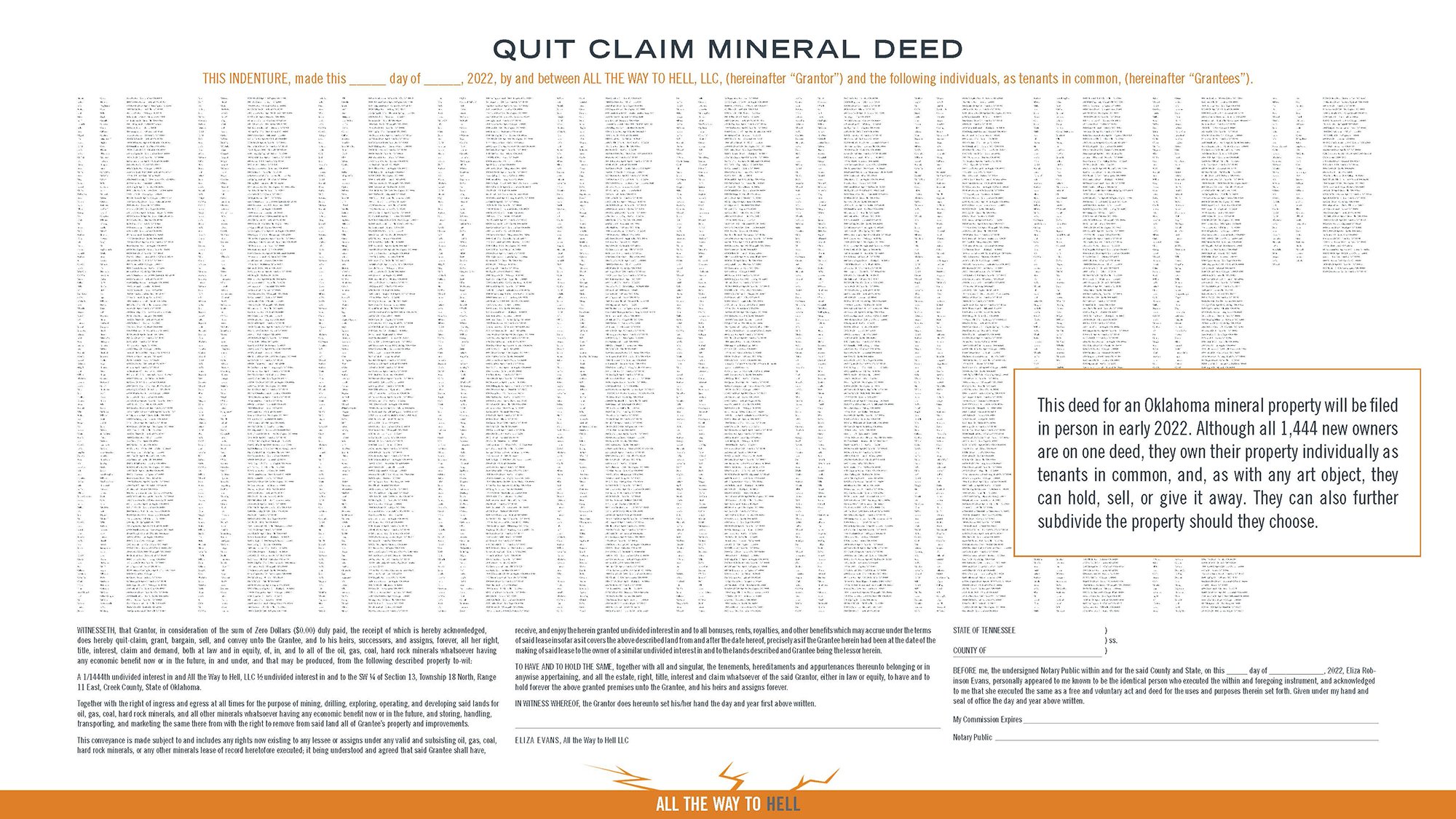

Evans then shows us the legal document that legitimizes the ownership and the right to explore and exploit the subsoil: a mineral deed of a property in northeast Oklahoma, in the traditional land of the Muscogee Nation, with a total of 1,444 signatory owners. This is the other, much more hegemonic archive.

Evans' background - she holds a Ph.D. in economic sociology from the University of Texas at Austin and has extensively researched the influence of fracking on the South Texas economy - demonstrates her commitment to a socially engaged art practice. Her goal as an artist isn't simply to "create and exhibit" particular objects, representations, or materialities but to activate critical devices where art becomes a place of encounters. These happen behind the scenes, over a series of bureaucratic operations the artist embarks on to make the project possible.

Evans' work is bound to bureaucratic interventions, creating a socially engaged art practice that activates collectively taking responsibility. Her project aims to uncover the power structure behind oil and gas development, thereby exposing and reclaiming the bureaucratic process, a tool designed to advantage white communities over minority groups and, in her words, "weaponizing it against the oil companies." The weaponization of bureaucracy is an invisible creative process where one's agency is used to short-circuit the system; Joseph Beuys called "social sculpture" art's potential to transform reality. Evans engages bureaucracy anew, inviting others to join a coalition of caring art activists.

In the 1990s, Evans inherited the three-acre property through her great aunt, land initially owned by Evans' great-grandfather, which he received, along with the mineral rights associated with it, as payment for a debt that he was due. Evans only became aware of her newfound wealth when an oil company contacted her to lease her mineral rights.

In general, property and mineral rights are owned by the same person. However, many people have transferred the latter without selling their property over the years. This has created a bit of a bureaucratic headache for companies, having to track down multiple individuals to secure the lease or purchase at least 50 percent of the mineral rights before they can begin fracking for oil and gas. This process of dividing the mineral rights is called fractionalization and remains an obstacle to fossil fuel development. Evans discovered that a sure way to avoid leasing her mineral rights was to split them among hundreds of people: "If the fragmentation occurs naturally through intergenerational wealth transfer," she told me, "(…) you take this thing they already hate and make it much worse." The oil and gas companies would be forced to locate, contact, and attempt to negotiate leases with each mineral right owner adding to the time and expense of developing a well. Her project would become more than an obstacle, a series of bureaucratic hassles that would lead them "all the way to hell."

Initially Evans considered selling each tiny mineral right but a lawyer informed her such an act would be illegal. Mineral rights are investments, like stocks, and one must have an SEC (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission) license to sell them or commit a felony.

Another obstacle to distributing each mineral deed one by one as people volunteered, would be the cumulative cost of filing fees; at $25 per filing, if she had gotten 1,000 participants, she would need $25,000. She decided to put all the names on one deed to file at one time which greatly reduces the cost of carrying out the project.

Cautiously following the law, using bureaucracy against itself, Evans engages in what she calls "uncivil obedience."

In the early stages of the project, the plan was to drive uncivil participation among colleagues and interaction with residency visitors and exhibition visitors she would meet while in artist residencies and shows held in various locations. With the onset of the pandemic, face-to-face contact disappeared, and Evans was able to reach and convince a broader community to sign up as co-owners of the mineral rights by moving the project online. It grew organically as she built her website, posting on non-traditional media spaces, promoting it through various artist talks, articles, and creating exhibitions. Thanks to efforts and a widely shared TikTok post, the project has nearly 7,000 participants (the count is still growing). Evans is now poised to replicate the project with new properties, increasing fracking disruption across the U.S.

To participate in her project (to own mineral rights), one needs to be a citizen or a permanent residence in the U.S. Certain outcomes of this project are the revelation of the power structure propping up the energy industry, a newfound awareness and a shared sense of responsibility that develops among participants.

In this regard, All the Way to Hell exemplifies the practice of what Donna Haraway calls response-ability; in Haraway's words, "is not something that you just respond to, as if it's there already. Rather, it's the cultivation of the capacity of response in the context of living and dying in worlds for which one is for, with others" (Haraway, 2015: 257). This sense of response-ability is what led Evans to perform, in her own words, an "expression of care: owning for caring not owning to exploit." With this, she suggests a way of living and organizing that is opposed to capitalism; to the demands of an extractivist economy. Evans is proposing a different perspective, which I would call an "economy of care"; it implicates choosing to play an active and critical role in the face of our privileges; to delve into the foundations of power, learn its inner workings, and consider non-existent rights: those of excluded minorities, of the land, rivers, mountains, and lakes. It is to think of a future beyond individual "needs", choosing the common good, beyond borders, regions, and countries.

Mineral rights and privilege, what is that?

"Property" comes from the Latin propriĕtas, which indicates the power, privilege, or right to possess. And etymologically," who possesses" (possidere, composed of potis' owner/power' and sedere 'to sit in power') "sits in power."

The privilege of sitting in power is not possible for everyone. As the Mexican writer and feminist Dahlia de la Cerda mentions, "rights are rights, but to access them one needs class and race privileges" (De la Cerda, 2020: 70).

Those who sit in power continue to do so by implementing centuries-old colonial structures designed to benefit those owning to exploit. All the Way to Hell makes the bureaucratic processes, the logic from which their systems are built, visible, revealing how class and racial privilege are linked to property and land rights. Extractivism implies the exploitation of unprivileged people, those who have no rights, as nothing more than a casualty of a profit-driven capitalist economy.

With this project, Evans challenges the powers-that-be by taking advantage of and subverting her position of privilege. She further invites the public-active-participants, who share in her privilege, to be complicit in this dismantling, to sit together, in an altered position of power.

Archive and power

Drawing from her artistic practice and her call to action, Evans shares kinship with artists whose practice explicitly invites and provokes engagement with bureaucratic and legal processes. Curator and writer Kari Conte, speaks of this as an "aesthetic of administration" based on everyday bureaucracy (Conte, 2019). These artistic practices were attached to institutional critique and, according to the jurist, historian, and criminologist, Katherine Biber, "did not merely resemble government records, but were made from them" (Biber, 2018: 289); these administrative origins were often the basis for the works' aesthetics. The installation All the Way to Hell aesthetically presents these bureaucratic features in the form of artifacts, such as the core samples that "scientifically" justify the exploration of the Earth and the mineral deed that legally legitimizes its exploitation. Evans' institutional critique, on the other hand, takes place within the energy companies' bureaucratic structure, albeit to different ends.

As legal anthropologist Annelise Riles points out, when we critique bureaucracy, we must be careful not to overlook "the very means by which bureaucratic processes compel...creativity in the first place" (Biber, 2018: 289). In All the Way to Hell, creation is carried out collectively by inviting the audience to consciously and actively participate in the bureaucratic sabotage.

Art critic Daniel Soutif uses the term présentification to describe the process by which found objects become art. In Evans's work, the invisible worlds of bureaucracy, legal processes, and ownership rights are presentified. Evans makes us question who appears in the archive and what kind of archive we choose to keep?

The archive is usually the place where the functioning of power is materialized. For Evans, the property records' archive "is a tool of white supremacy." Evans is trying to give testimony, to leave a document that lays the groundwork for actions that cannot be erased. All the Way to Hell is a "betrayal" of the hegemonic system, an attempt to merge with erased histories. Haraway further states that response-ability is directly bound with absence and presence, about who lives and dies (Haraway: 2019: 57). Like Evans's, there are artists whose projects use environmental causes integrally and as an entry point to attack the colonial narrative of capitalist dominance via dispossession and disenfranchisement.

Brazilian architect and urbanist Paulo Tavares and the Swiss artist, author, and video essayist, Ursula Bieman first come to mind with a research project called Forest Law. They archive the juridical processes surrounding Ecuador's Kichwa People's attempt to recognize Earth as a subject of rights. It argues the importance of considering the forest as a living being. In the same spirit, Brazilian artist Maria Thereza Alves's project, in which she explores the colonial dispossession of the lands and waters of communities in the Valley of Mexico and questions the passivity with which the inhabitants of Mexico City accept the disappearance of a lake, forgetting the history of conquest and cultural resistance.

Together with Evans, these artists articulate a common issue: to reannex a forgotten, under-recognized, invisible, or erased knowledge and present it in a disruptive way. These artists take on the role of facilitators, providing tools for constructing a more just and responsible reality.

To mineral rights, All the Way to Hell is akin to Spanish artist Lara Almarcegui's piece: "Derechos Mineros" (Mining Rights). Almarcegui obtained mining rights in Austria and Norway through a lengthy bureaucratic process. She aims to prevent the exploitation of these lands, which she can achieve as long as she holds on to the mining rights. Like Evans, she raises awareness of the power structure that rules the faith of the environment by exposing, in this case, the mining conditions in Europe. The fundamental difference between Almarcegui's piece and Evans' is that in All the Way to Hell, the artist goes a step further and invites the public to participate in disruptive processes, thus accentuating the importance of small, cumulative actions, essential to crack the system.

Eliza Evans turns our gaze to our feet and invites us to participate in a collective response as a form of resistance. All the Way to Hell is an attempt at fracturing a world that no longer works. It bets on futures in which we are actively responsible for our actions, where we understand that sitting in power implies building worlds, policies, laws, and economies based on care. It is a future where it is possible to dismantle the invisible rights (of communities, of nature, of the environment), where we create ways of socializing with other histories. Foreshadowing a future built on collective gestures allows us to imagine a world that can survive us. If poet, Joy Harjo, is correct and “The land is a being who remembers everything,” then what will it say about us?

References:

Biber, Katherine (2018), “The Art of Bureaucracy: Redacted Ready-mades” in Law and the Visual. Representations, Technologies, and Critique, ed. by Desmond Manderson, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Conte, Kari (2019), Paperwork: Administrative Practice in Contemporary Art, International Studio & Curatorial Program, Brooklyn, NYC [online: https://iscp-nyc.org/event/paperwork-administrative-practice-in-contemporary-art].

De la Cerda, Dalia (2020), “Feminismo sin cuarto propio”, Tsunami 2, México: Editorial Sexto Piso.

Haraway, Donna (2019), Seguir con el problema. Generar paretenesco en el Chthuluceno. Bilbao: consonni.

Harjo, Joy (2015), “Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings”, [online: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/141847/conflict-resolution-for-holy-beings].

Kenney, Martha and Donna Haraway (2013), “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulhocene” in Art in the Anthropocene. Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies, United Kingdom: Open Humanities Press.

Eliza Evans experiments with sculpture, print, video, and textiles to identify disconnections and absurdities in social, economic, and ecological systems. The initial parameters of each work are carefully researched and then evolve as a result of interaction with people, time, and weather. Her work was exhibited at the Thomas Erben Gallery, NYC, Austin Peay State University, Clarksville,TN, Chautauqua Institution, Chautauqua, NY, Edward Hopper House Museum, Nyack, NY, and Purchase College, Purchase, NY. Residencies include the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis, UC Santa Barbara (2020), Bronx Museum AIM, and Franconia Sculpture Park, Shafer, MN (both 2019).