Wild Mythologies

As children of early 90s rural Britain, my friends and I would freewheel around our neighbourhood on rusty bikes, playing around empty properties. We invented, and scared ourselves with, stories of escaped convicts and malevolent ghosts. We fabricated magical other worlds within and beyond the walls, woods and hills around us. We believed in these stories, and in our ability to shape the world, with a confidence that was beyond certainty. It was serious play – we were finding ways to understand the vast possibilities in a life, and a growing consciousness of the darkness in the world. Through the lexicon of these stories, we could dream together and share our fears in a way that allowed us to save face and find humour. It was fun, but just as important, it was a matter of surviving and thriving.

From the micro-cultures of childhood to religious festivals, art, literature and global histories, storytelling has been at the heart of the human experience as far back as we can decipher. To craft a story is to convey meaning through symbols, visual, aural and otherwise. We might not believe a story in literal terms, but it can communicate a sense of a lived reality in emotive and sharable ways. Stories and speculative fictions can help make sense of the world and suggest new cultural norms. But they can also reinforce historical patterns and attitudes, further embedding existing cultural values. Folklore can bring a community together, and propaganda divide it. The story, as a form, can be held differently – legends take lightly the tale's veracity, and fake news grips the attention of its viewer.

In simple terms, a myth is a story that explains a culture. Responding to environmental discourses within contemporary art, Wild Mythologies is a series of artist conversations that can turn our attention to how, why, and by whom stories are being told. At the same time, the series aims to hold space for stories and folktales that foster care, healing and hope, even a sense of exuberance and vitality, of ‘wildness’. When we turn to arts and culture to find new kinds of mythology, we are participating in an experience of curiosity and creativity in which the process of ‘fabrication’ is not concealed; it is part of the beauty and power of the work. The openness required to become immersed in an artwork and fully experience it can change a viewer’s understanding of a place, a person, a situation. A minute shift in worldview, caused by an artwork, can shape choices around how we listen and respond to others, perhaps even influencing our political rationale.

Of course, much has been written about myths. The famous collection of essays by Roland Barthes, Mythologies, explores pop culture phenomena, from eating to wrestling, to expose the constructed meaning within the quotidian. He looks at how myths, themselves a language, shape our world. But for Barthes, myths ‘impose’ meaning (1957, p.115), aiming to preserve reality as an image. However, he writes that: ‘wherever man speaks to transform reality and no longer to preserve it as an image, wherever he links his language to the making of things, metalanguage is referred to a language-object, and myth is impossible’ (1957, p.146). What then of art, of visual storytelling, that offers new ways of seeing the world? Does art seek to transform reality? Or to preserve it as image? Perhaps the duality of art, its concreteness and ephemerality, puts it in an interesting position with regard to storytelling and myth.

Each episode of Wild Mythologies features two artistic perspectives, each responding to a theme or issue differently, with each artist posing a question for the other. The narrative arc of the series begins grounded in a specific space (a nuclear power plant) and grows around and with the issue of toxic waste and energy consumption. The first episode, ‘Dark Meditations’, asks viewers to be fully present and alert to the magnitude of our environmental issues. Developing into the second episode, ‘Stories of Deep Time, we encounter artists initiating healing rituals and composing stories for humans thousands of years into the future, warning of toxic waste disposal sites. In the third episode, ‘New Folklore’, discussions of alternative narratives encourage listeners to critically engage with existing mythologies and imagine new ways of being. And episode four, ‘Transformative Storytelling’, features discussions with artists sustaining and forming communities around their practices.

Wild Mythologies has been inspired by the words of anthropologist Anna Tsing, who writes about the precarity of living in a late-stage capitalist culture. She reminds us that: “Precarity means not being able to plan. But it also stimulates noticing as one works with what is available. To live well with others, we need to use all our senses, even if it means feeling around in the duff.” (2015, p.278). Acknowledging the uncertainties and anxieties causing (and caused by) ecological decay, Wild Mythologies is hopeful; it looks at ‘what is available’ to us and how we might ‘live well with others’.

‘Dark Meditations’ brings together artist Nastassja Simensky and electronic music composers Will Frampton and Rhiannon Bedford (The Keeling Curve). In 2022, Nastassja, Will, and Rhiannon collaborated on an audio-visual work, Ythancastir: Atoms on the Wall, developed on the site of a decommissioned nuclear power station on the Blackwater Estuary in the UK. Three years later, they reflect on the industrial afterlife of the power station and the role of art in drawing painful or difficult things to the surface. The artists discuss the importance of situating oneself within a particular site, learning about it, listening to it and documenting it. Risking a clash with the security guards to create the soundscape (which includes the sound of the artists hitting the iron bars that surround the power station), the artists wanted to call attention to the colonial legacies of extraction within nuclear history and the invisible toxicity of radiation. The beauty and brutality of the irradiated site are captured using military-grade cameras, creating a work that is both compelling and jarring. Each artist brings their own story and approach to this collaborative work, which was made possible with the support of a religious community, Othona, founded after World War II as a rural retreat to allow for difficult conversations to be held. The singing of the Othona community brings their presence into Ythancastir: Atoms on the Wall, giving the work a quiet spiritual and political energy.

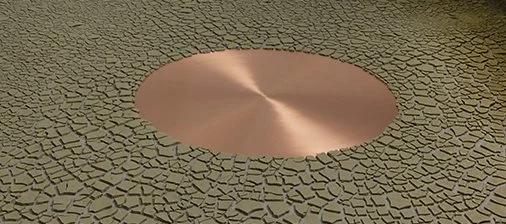

‘Stories of Deep Time’ invites viewers to contemplate geological time frames that span millions of years. From our perspective as finite beings, it is perhaps impossible to grasp time as endless, and to talk about ‘deep time’ is to engage in a conversation at once philosophical and ethical. Artist Veit Stratmann visualises two kinds of deep time – one that stretches back into history and one that unfolds into the future. For Veit, these times have a different quality, and situated between them, he feels unable to connect them. However, in A Hill, he turns to ‘future deep time’, to consider how to prevent future generations from exposing a nuclear waste disposal site in France, designing a speculative landscape in response to an artist call-out initiated by a nuclear energy company. Approaching the project with knowing criticality, Veit’s proposal to destroy woodlands and to create a hill, to partition the waste disposal site and bury it deeper beneath the earth, caused ripples of dissent throughout the community living near the site. Veit’s proposal was intentionally charged. He wanted to raise significant questions about the ethics of nuclear energy production and the rationales that shape waste disposal. The ritualised nature of A Hill can be understood as a promise, and ‘a promise is something which structures futures’, reflects Veit. But although artists can produce and communicate memories, the meaning of artworks and cultural experiences can be modified or recontextualised over time. For ceramicist Aimee Lax, this is true of historic ceramic objects, fragile pots made of earth that can be buried and revealed hundreds of years later to carry information into the future, but what information? And how is it to be interpreted?

Aimee, an artist in residence at London’s V&A Museum in 2020, invited audiences to explore the glass collection in the V&A with a UV torch to see which of the objects would fluoresce under the torchlight, to reveal uranium glass. Hidden in plain sight amongst the decorative objects, the glow of uranium glass was scattered throughout the collection. Aimee’s residency at the V&A coincided with the Covid-19 lockdowns in the UK which meant that the gallery space became ‘more of a laboratory space’, the public could not visit the exhibition. Aimee works with bentonite clay, which is also used in nuclear waste disposal – where it is dug up to be buried again, on top of spent nuclear fuel as a protective layer. As someone who works with minerals, earth, and clay, she was gifted a honey jar filled with uranium oxide, which currently sits near her desk in her studio, awaiting a ritualised disposal.

From ritual to folklore, the next discussion, ‘New Folklore’, features artists Angeline Marie Michael Meitzler, and Stephanie Deumer, whose works deconstruct stories to open space for the emergence of new narratives. Stephanie’s work A Diamond is Forever explores the gendered presumption that feminine-presenting identities desire to own diamonds. Spotlighting misogynistic mythologies, her work Spooky Action at a Distance draws attention to the popularization of ‘vanishing women’ in Victorian magic shows, and how this coincided with the census revealing a greater number of women than men at this time in history. Stephanie points out how the figure of the disembodied woman continues in contemporary culture in the form of virtual assistants Siri and Alexa, to be conjured up when desired. Critically engaging with creation of myth, Stephanie looks at social constructs as mythologies, raising existential questions about meaning-making and one’s place in the world.

Also exploring positionality, Angeline Marie Michael Meitzler’s film The Bird, The Girl and The Typhoon reclaims mythologies relating to the red kindling bird, representative of the typhoon season passing and harvest time in the Philippines. The protagonist of the film is an elderly Filipino nurse, who shapeshifts into a bird, ‘transforming into her own internal force’ and source of safety. Angeline speaks of the ‘present history’ of colonialism, the impacts of US occupation of the Philippines, which included the establishment of nursing schools in which women were trained to become nurses and learn English to prepare for migration to the US. Subverting this colonial narrative, The Bird, The Girl and The Typhoon draws attention to the power and strength of the kindling bird, using this as a symbol to communicate a sense of resilience and to remythologise stories of migration.

The final episode, ‘Transformative Storytelling’ turns to two more ancestrally-inspired practices – Yiou Wang’s ‘techno-animist’ digital works that combine animist and modern ways of seeing the world, and Dennis RedMoon Darkeem’s installations, performances and socially-engaged works. Yiou, influenced by the writing of Jorge Luis Borges, explains: ‘In order for people to understand your story, you must lead them into the world where the stories stem from’. Yiou’s approach has been shaped by East Asian culture and global modernism reflecting how ‘animist ways of seeing the world are still very much alive.’ Their work explores ‘ancient future myths’ using digital technologies to shape perceptions of land and water. Our discussion of Water Always Goes Where It Wants to Go centres on the hydrofeminist idea of the land as a body of water. Viewers are invited to reflect on how water is the ancestral entity that is shared among all life. As founding artistic director of Mixanthropy Studio, Yiou often works collaboratively to build new worlds, folding together the ancient and the speculative to forward new approaches to storytelling that are at once spiritual and ecological.

The question of how we continue and extend ancestral stories is at the heart of Dennis RedMoon Darkeem’s practice. Working across a range of media, Dennis creates public art, sculpture, photography, collage, sound and performance work, as well as community practices. Dennis describes how interactions and language are carried in our DNA, but that without community it is hard to keep our understanding of these alive, to keep traditions alive. Dennis’ Indigenous Yamasee Yat’siminoli and African-American cultural heritage is explored not only through the forms of his work, for example, his creative reworking of patchwork traditions in Patchwork Travelers at Penn Station, but through the practice itself, which includes educational and participatory works. ‘Relationships based on interaction are more important than fixed identities,’ says Dennis, suggesting that relating to each other through listening and sharing our stories (focusing on how we are) is more important than asserting a persona (focusing on who we are). Dennis reflects on how the convenience of modern life can cause us to forget about our ancestors' struggles to survive and thrive. He wants to remember this, and respond to these stories, to build a ‘living legacy’.

Wild Mythologies invites us to take apart and question the written, verbal and visual narratives that shape our understanding of the world, and to make space for new stories to unfold. Greater awareness of the myths that shape our consciousness, from the micro-cultures of childhood and family folklore to the macro-cultures of national traditions and global modernity, can help us further realise our own agency. Moving away from individualistic expressions of agency, Wild Mythologies spotlights how working together as a collective can facilitate a deeper understanding of our histories as they stretch back into deep time, and our futures, as they unravel beyond our comprehension. Art, as a form of visual communication and storytelling, is always ‘with’ others. And as we listen to the quieter storytellers around us, and together fabricate new myths, we can develop confidence beyond certainty and resilience to ‘feel around in the duff’ of climate decay to find ways to live well together.

Jessica Holtaway

May 2025.

——————————

Bibliography:

Barthes, Roland. (1957) Mythologies, trans. Annette Lavers, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. (1972 ed.)

Tsing, Anna. (2015). The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

——————————

Image list:

All images Courtesy of the Artists.

Image 1: Angeline Marie Michael Meitzler The Bird, The Girl, and The Typhoon

Image 2: Dennis RedMoon Darkeem Patchwork Travelers

Image 3: Aimee Lax Repository -The Final Resting Place

Image 4: Veit Stratmann A Hill

Image 5: Stephanie Deumer Spooky Action at a Distance

Image 6: Yiou Wang Water Always Goes Where It Wants to Go

Image 7: Aimee Lax Uranium glass stems (detail)

Image 8: Nastassja Simensky, Will Frampton, and Rhiannon Bedford Ythancastir: Atoms on the Wall (live)