On the Edge of Time

In the 1976 utopian novel “Woman on the Edge of Time,” author Marge Piercy’s protagonist is presented with two alternative futures: in essence, an ecological utopia, and an apocalyptic dystopia. It’s with this concept that the Prospect Art Broadcast series, On the Edge of Time, finds its starting point.

“Woman on the Edge of Time” is considered a classic of utopian speculative science fiction and a feminist classic which explores themes of social justice and utopian visions. The story’s protagonist, Consuelo "Connie" Ramos, experiences both a dystopian future and a utopian future through her connection with Luciente, an emissary sent from the year 2137. The utopian future, known as Mattapoisett, presents a society that challenges gender norms, promotes equality, and prioritizes communal decision-making. The society values the wisdom and leadership of women, echoing the influence of indigenous cultures that revere women's roles as environmental caretakers and leaders. This utopian future challenges dominant power structures and prioritizes communal decision-making. The community in Mattapoisett engages in participatory democracy, emphasizing the voices and agency of all individuals in shaping their collective destiny.

The novel centers gender equality and places an emphasis on communal decision-making, envisioning a future that challenges oppressive systems and centers the voices of marginalized communities. Each of these themes were presented as part of the events planned for On the Edge of Time.

The Series

The concept of making choices that can lead to varied results for the future of humanity is present throughout the series, whether as an ecofeminist response to the climate crisis, as in the work of Carolina Montejo, as speculation and new world-building after an ecological failure as in the work of Santiago Tamayo Soler, or as a practice of collective governance, as in the work of Dora Durkesac.

Each of these artists’ practices inspired live, interactive events as part of On the Edge of Time, a series of web-based events consisting of artist talks, workshops, and screenings addressing the future of humanity in symbiosis with nature. Inspired by historical utopian thinking, the series sought out frameworks proposed to confront current and future ecological challenges. With three live events between October 2022 and April 2023, programming explored research on systems created in symbiosis with the natural world and speculative ecological futures as inspired by utopian visions.

Rizomas

The first event in the series was a screening of the experimental film Rizomas (2021) by Carolina Montejo. Montejo is a Colombian-American artist and filmmaker, educator, and climate justice advocate who also serves as a lecturer in environmental studies and film studies. A Q&A with Montejo followed the screening, where we discussed the themes of the film and the artist’s process.

Rizomas is an experimental documentary that travels through diverse imaginaries, memories, and realities of nature and their overlap between plant, human, and animal existence. The forty-two minute film is presented as an intriguing mix between a traditional documentary style and experimental eco cinema. The storyline shifts between a series of intimate documentations, a political manifesto, a 3D animated utopia, a collaboration with a network of urban farmers, as well as a metaphorical dance sequence shot in 16mm. Expanding through an eco-feminist ethos, Rizomas moves within the plurality of language, place, and time to reveal the constancy of the material world and its interdependent possibility for renewal.

Ecofeminism

One of the ways in which Montejo’s film proposes frameworks for building more sustainable systems is through feminist eco-pluralistic practices and human, plant, and animal embodiment and interdependence. Ecofeminism, as a framework that recognizes the connections between the exploitation of nature and the oppression of women, emphasizes the need for a holistic and intersectional approach to social and environmental justice.

For example, Montejo’s film, in part, explores Red de Mujeres Construyendo Futuro (Network of Women Building the Future), a collective of women urban farmers who work towards building sustainability in their Colombian communities. The organization incorporates ecofeminist principles in their work, intertwining environmental sustainability and women's empowerment. They provide training, education, and resources to women, equipping them with the skills and knowledge needed to empower them to actively participate in decision-making processes. Through cooperative projects, they work towards improving access to healthcare, education, clean water, and other essential services.

Through their various initiatives and programs, the network addresses social, economic, and environmental challenges, aiming to create positive and sustainable change, as they recognize the interconnectedness between the well-being of communities and the health of the environment. They undertake initiatives that promote sustainable practices, such as organic farming, waste management, and conservation of natural resources. By integrating ecological principles into their work, the network seeks to protect the environment, preserve biodiversity, and mitigate the impact of climate change, thereby ensuring a healthier and more sustainable future for their communities.

Red de Mujeres Construyendo Futuro also advocates for policy changes and social transformation. The network actively engages in dialogue with policymakers and community leaders, advocating for gender-responsive policies, women's rights, and social justice. By amplifying the voices of marginalized women and challenging systemic barriers, the organization works towards creating a more inclusive and just society for future generations.

Red de Mujeres Construyendo Futuro embodies ecofeminist principles by placing an emphasis on intersectionality, valuing care and relationships with humans and with the natural world, and in challenging established power dynamics. By integrating these ecofeminist principles into their work, Red de Mujeres Construyendo Futuro promotes ecological stewardship and challenges patriarchal systems that perpetuate inequality and environmental degradation.

The influence of ecofeminist practices on Montejo’s work was the perfect starting point for the series that provided the series with concrete responses to the proposal for frameworks to confront ecological challenges, and in Montejo’s research, opening up the discourse on symbiotic relationships between humans, plants, and animals.

Symbiotic Systems

When I approached Montejo about screening her film Rizomas, we discussed one of the influences on this program, the significant impact of systems built by indigenous communities in symbiosis with the land. These systems recognize the interconnectedness of humans, the environment, and all living beings, rejecting the exploitative and hierarchical relationships prevalent in capitalist systems.

Indigenous communities have a rich tradition of passing down ecological wisdom from one generation to another, ensuring the continuity of sustainable practices. This knowledge includes techniques such as regenerative agriculture, agroforestry, and seed saving, which prioritize the long-term health and productivity of the land, promoting ecological resilience for future generations.

Our exploration of ecofeminism can also be exemplified in indigenous cultures that recognize the inherent connection between the well-being of women and the environment. For example, the Chipko movement in India, led by rural women, embraced tree-hugging as a form of resistance against deforestation. Their actions highlighted the crucial role of women as environmental stewards and protectors. Similarly, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, a matrilineal society, emphasizes the importance of women's leadership in decision-making processes regarding land and resource management. The consensus-based decision-making processes of many indigenous societies ensure that all community members, regardless of gender or social status, have a voice in shaping sustainable practices. This approach fosters a sense of shared responsibility and encourages the equitable distribution of resources, challenging the dominant systems that perpetuate inequality and exploitation.

Another example is the concept of biocultural rights, championed by indigenous peoples. Biocultural rights recognize the interconnectedness of cultural and ecological diversity, affirming the rights of indigenous communities to maintain their cultural practices, traditional knowledge, and connection to their ancestral lands. This framework respects the autonomy and self-determination of indigenous peoples, ensuring their equal participation in decision-making processes related to environmental governance. By embracing and incorporating these examples of ecological futurity, ecofeminism, and equality from the systems created by indigenous communities, a more sustainable future that respects the rights and wisdom of all people can be built.

Retornar

For the second event in the series, Santiago Tamayo Soler led an interactive workshop based on his video work Retornar (2021), which he generously made available for viewing on the Prospect Art website during the run of the series. Narratively structured as a video game, the twenty minute video work narrates the story of the nine last living humans on Earth and their journey towards a big “reset.”

Retornar (Spa. To return, to come back) is set in a fictional, eco-pessimistic Andes in the year 2222, where Latin America has nothing else to give. As Tamayo Soler describes it, its soil has dried up and the atmosphere has become increasingly dangerous. After a big war driven by an extreme exploitation of natural resources, the surviving characters wander around a dystopian Andean landscape, aimless and alone, with no other purpose but to spend their day going through different puzzles and loading screens, until they are summoned by a mysterious blue orb that will transport them into a digital celestial world where - after a big celebratory “last dance” - they will be forced into becoming the seeds for a new generation.

Interested in fiction/nonfiction, narrative devices, and live action, Tamayo Soler's most recent work overlays digital footage and modified video games to create pixelated universes home to Latin American, immigrant, queer stories of a radical futuristic fantasy. Retornar was made through a multilayered process. The world itself was built through a mixture of scenes created in The Sims 4, SketchUp, Photoshop, and incorporated real footage shot in front of a green screen. The scenarios were built using an isometric perspective to mimic early 8 bit video games, as well as early life simulation games, and video chat universes.

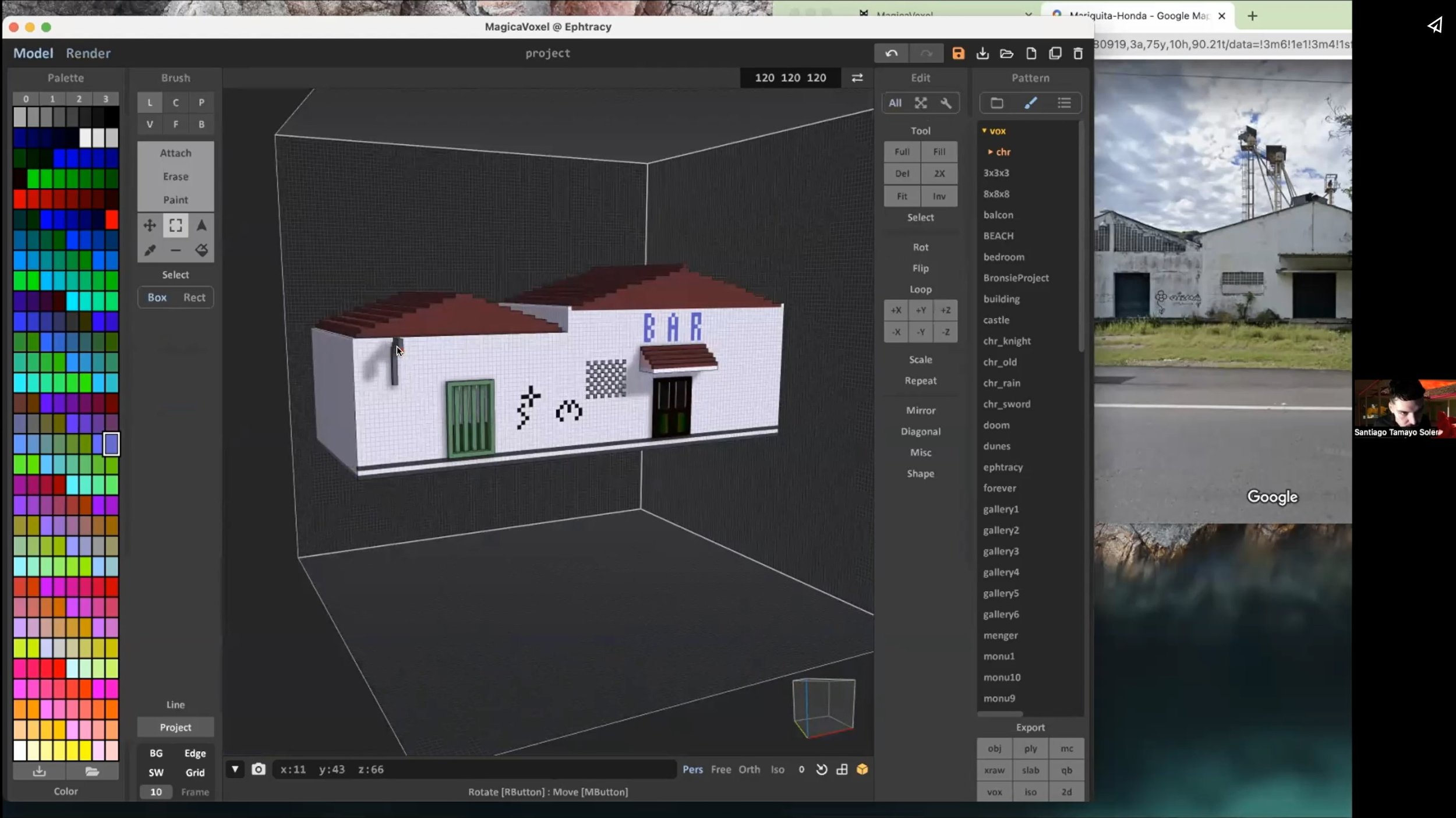

Using MagicaVoxel, the artist invited participants in the workshop to contribute suggestions on additions to a collectively built scene set in a futuristic Latin America. Participants were able to ask questions, comment, and make suggestions. At the end of the workshop, participants were able to download a .png version and a .png isometric version of the final scene from the Prospect Art website.

World Building and the Online Workshop as Community Builder

Santiago Tamayo Soler’s interdisciplinary work lent itself well to this model of event. As a performance artist, the participatory aspect of the workshop allowed him to work instinctively as a reaction to attendees’ comments and suggestions, with a pre-planned scene that was able to be customized to participants’ liking.

The workshop was based on live streaming video game players on platforms like Twitch, where their audience, consisting of both fans and provocateurs, contribute suggestions, questions and comment on the streamer’s game playing. In this model, participants are often shielded by anonymity, opening up the possibilities of their contributions without being judged. Participants were not asked to have their cameras turned on, and could potentially use any name over Zoom that they chose. It’s with this set of circumstances that participants were encouraged to feel comfortable enough to participate to the fullest extent.

In theory, online workshops can provide a platform for diverse voices and perspectives to be heard, transcending geographical boundaries and amplifying marginalized voices in a purposefully egalitarian medium. Through interactive sessions, facilitated dialogues, and collaborative activities, online workshops can be a transformative medium that allow for the co-creation of knowledge, facilitate the exchange of ideas, and support camaraderie among its participants. They have the potential to reach a broad audience and engage participants from diverse backgrounds, fostering a sense of global community and shared responsibility.

In practice, the impact of online workshops is not solely determined by the facilitators but is also deeply influenced by the active participation and engagement of individuals. Their willingness to share, listen, learn, and collaborate shapes the outcomes of these workshops. Through their active involvement in the world building workshop, for example, participants were encouraged to contribute to the co-creation of an eco-pessimistic scene, one that is representative of a radical, imaginary future. However, as in the Dora Durkesac’s workshop which took place next in this series, participants can also contribute to an imagined community that is representative of an inclusive, sustainable, and equitable future. The transformative power of online workshops lies in the agency of individuals to shape the narratives, strategies, and actions that emerge, fostering a sense of collective agency and responsibility in building a better world.

Ecosystems: Rehearsing Collectivity

The April 2023 iteration of Dora Durkesac’s workshop for this Broadcast series, Ecosystems: Rehearsing Collectivity was in part inspired by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s book, “The Mushroom at the End of the World,” which offers insights into the potential of resilient and adaptive systems to confront ecological challenges.

One key contribution of the book is its exploration of systems created in symbiosis with the natural world. Tsing examines the intricate relationship between the matsutake mushroom and its surrounding ecosystem, highlighting the ways in which human activities and natural processes intertwine and coexist. By emphasizing the ecological interdependencies and the ways in which human and non-human actors shape and are shaped by their environments, Tsing challenges the notion of a strict divide between humans and nature.

Tsing explores the concept of salvage accumulation, where marginalized communities, such as migrant foragers, engage in practices of gathering and trade that operate outside the confines of traditional capitalist systems. This framework suggests that alternative modes of production and exchange can exist outside the destructive cycles of capitalist consumption, offering potential paths towards sustainable and equitable futures.

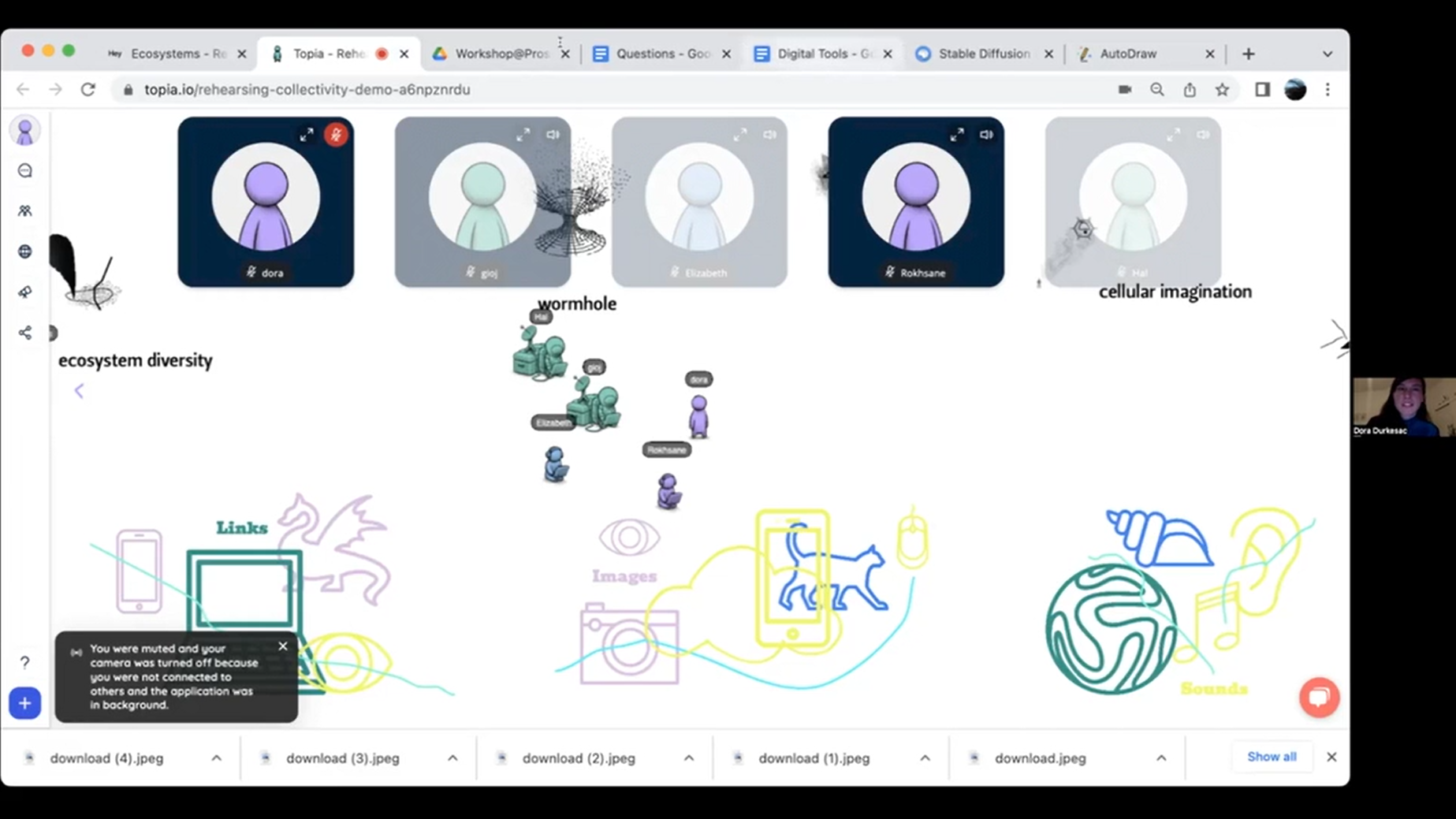

Held over Zoom and the metaverse platform Topia, the interactive and collaborative workshop aimed to help us imagine collective living through co-creating systems, and led participants in a series of practices that led us toward building an exploratory community where natural and digital structures regenerate human ones. We “rehearsed” personal and collective scenarios, which began with reflecting on browsing history, continuing with chat poetry, and contaminating ideas. During this process, we used simple digital apps in 3D modeling, image, or sound generation and choreographed them via desktop to create a temporary collaborative ecosystem.

Collaborative contamination and Co-authorship

As a vehicle for community building, the workshop model fosters co-authorship and collaboration. It encourages communal decision-making and equality. As a defining principle of ecofeminist discourse, the workshop model similarly encourages a collaborative and participatory approach. Just as ecofeminism emphasizes the importance of collective action, collaboration, and participatory decision-making, Durkesac’s workshop emphasized a collaborative approach by fostering engagement, encouraging camaraderie, and supporting participatory processes in decision-making for the group’s imagined community.

Among Durkesac’s inspirations behind her ongoing workshop series for Ecosystems: Rehearsing Collectivity are concepts including rhizomatic sharing, thinking through liquidity, porous community, micro-empathy, swarm behavior, and cellular imagination. Among these is also the concept of contamination as collaboration, taken from The Mushroom at the End of the World. Contamination as collaboration refers to the idea that seemingly disruptive or contaminating elements can foster unexpected collaborations and symbiotic relationships in ecological systems. It challenges the conventional understanding of contamination as purely negative and highlights the potential for productive encounters and regeneration that arise from disturbances in capitalist and ecological landscapes. This concept underscores the interdependence of organisms and invites us to reevaluate our assumptions about what constitutes a healthy environment, recognizing the transformative potential and resilience that can emerge from disruptions in ecological systems.

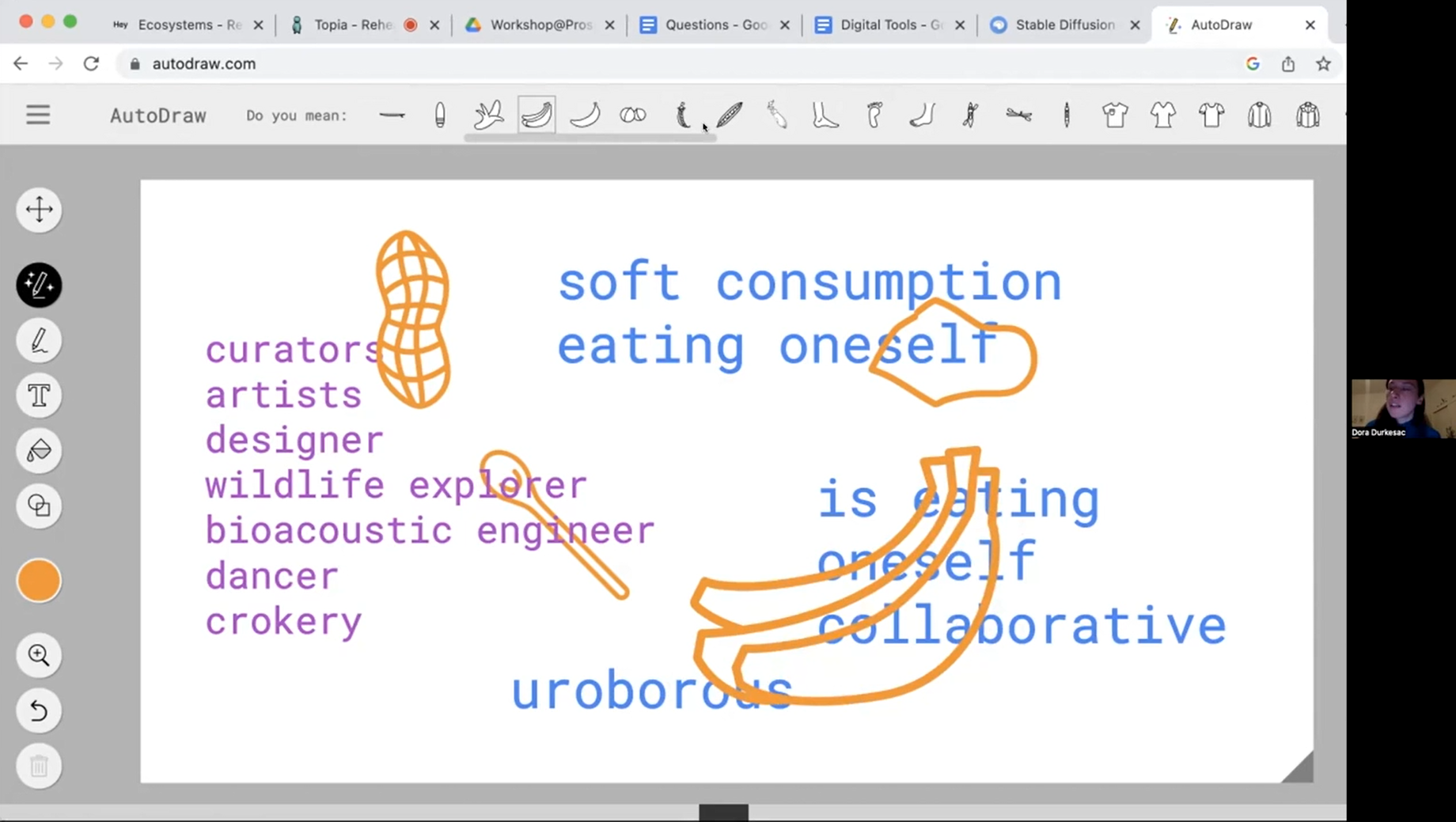

Durkesac’s open-ended workshop was structured through collective activities: sharing our browser histories with other participants, building on these concepts by using generative AI apps to visualize and further contextualize concepts we explored, and co-creating a fictional community based on our communal interests and identities. Just as in the workshop led by Santiago Tamayo Soler, the participation of individuals in this online workshop was integral to its outcome, possibly even more so, as there was no pre-prescribed community built for the participants, and it was completely customized to the interests and explorations of its audience. In keeping with the theme of the series, future results were directly impacted by collective choices made by participants.

Conclusion: The Medium of Virtuality

An essential element of this series was the impact of technology, not only on the technical aspect of the series but on the theme as well. In hopes of fostering meaningful connections, sharing knowledge, and practicing the principles inspired by the artists’ frameworks for ecological sustainability and systems created in symbiosis with the natural world, I sought out media that I believed would be the most engaging for an online audience, based on other models of virtual engagement, including Instagram Live and live streaming on Twitch.

Although unpredictable at times, the online medium is mostly egalitarian in nature, and the artists actively sought out ways to encourage collective decision-making and inclusive engagement. Each of the three events led participants from one program, Zoom, to another program to view a film screening, contribute to a built 3D model, or immersing oneself in a metaverse. The act of requiring attendees to switch from one program to another, while potentially difficult, acted as another layer of engagement, a way of inviting participants to come along for the journey.

Prospect Art’s Broadcast program was created to provide a virtual space for online public presentations in the form of discussions and interviews. For On the Edge of Time, the focus on interactivity in these online events was purposeful in striving for a global forum for critical discussion. Choosing the medium of online workshops presented an opportunity to draw immediate connections to the series’ themes of communal governance, equality, and cultural diversity and plurality. Outcomes were often directly impacted by the participants in each workshop or Q&A, and the format of these events was intentional in centering the audience in active engagement with the themes and concepts presented as part of the series.

Themes of ecofeminist practices, symbiotic systems inspired by indigenous communities, collective world building, and collaborative contamination all feature ties to communal decision-making processes and egalitarian social structures. In contrast to hierarchical and centralized models of power, these themes prioritize inclusivity and consensus-building. These principles have influenced utopian thinkers who envision societies based on participatory democracy, equitable distribution of resources, and social cohesion. Utopian visions drawing inspiration from many of these principles often seek to challenge social inequalities and empower marginalized communities. They also seek to preserve cultural diversity, recognizing the importance of multiple worldviews and knowledge systems. It was with this intention that the artists who presented as part of this program sought to engage their audience.

Rokhsane Hovaida,

June, 2023.

All images courtesy of the artist unless otherwise notedImage List:

1- Carolina Montejo, Rizomas (still), 2021

2- Carolina Montejo, Rizomas (still), 2021

3- Santiago Tamayo Soler, Retornar (still)

4- Workshop with Santiago Tamayo Soler

5- Workshop with Dora Durkesac on Topia

6- Workshop with Dora Durkesac, using AutoDraw

—————————————————————

Link to “On the Edge of Time” Broadcast segments.

—————————————————————