“Can Drawing Be Political?” Andrej Mirčev on Jen Durbin

After the cloud had cleared during the afternoon, Friday, November 22, 1963, in Dallas was a bright sunny day. The crowds had gathered along the main street as they expected to see the 35th President of the United States passing down to Trade Mart, where he was supposed to have lunch and meet with Texas Democratic Party members. Yet, the President never arrived at the meeting. The motorcade consisting of three cars drove slowly from Dallas Love Field before it stopped at Dealey Plaza. An estimated crowd of 150,000 to 200,000 people had been waving at him sitting in an open-top Lincoln-Continental limousine together with his wife Jackie Kennedy, Governor John Connally, and his wife, Nellie Connally. At the end of the parade, the President was still waving back when a bullet "entered his upper back, penetrated his neck, and slightly damaged a spinal vertebra and the top of his right lung. The bullet exited his throat nearly centerline just beneath his larynx and nicked the left side of his suit tie knot." At 12:30 p.m., he was fatally shot from a 6.5x52mm Carcano Model 91&38 infantry rifle and was declared dead half an hour later. As it was later concluded by the Warren Commission and labeled as the "Single-bullet theory," one high-velocity bullet killed the President and seriously wounded Governor Connally.

Equipped with an 8mm Bell&Howell Zoomatic 414PD Director Series Model and with a Kodak Chrome II safety film, the Ukrainian-born American Abraham Zapruder stood on top of a 4-foot concrete block near the park where the motorcade would pass. At first hesitant, because it was raining for the whole morning, Zapruder decided to shoot. The clouds had drifted away, and the scene was brightly lit by the sun just passing the zenith. He had a perfect position. As the cars turned from Housten street onto Elm Street in front of the Texas School Book Depository, where the bullets were fired from a sixth-floor window, he started filming. The 26.6 seconds or 486 frames capture the assassination, making the footage the most complete and reliable document of the event. Using the film as evidence, the investigation was able to reconstruct the details and identify the exact timing of the shooting and the precise trajectory of the 6.5 millimeters, 161 grains, round nose military style full metal jacket bullets hitting the President at about 1,700 feet per second.

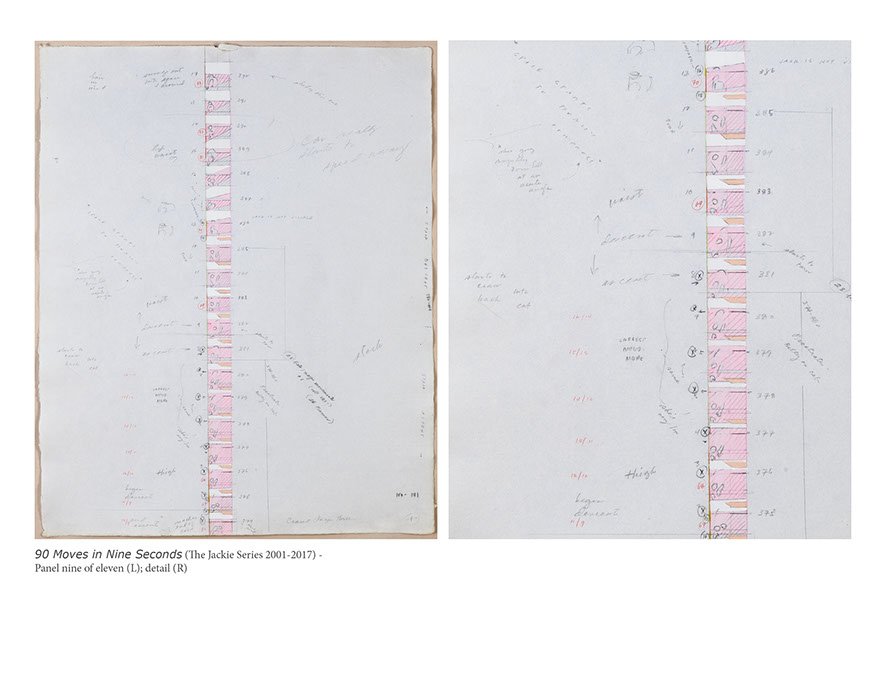

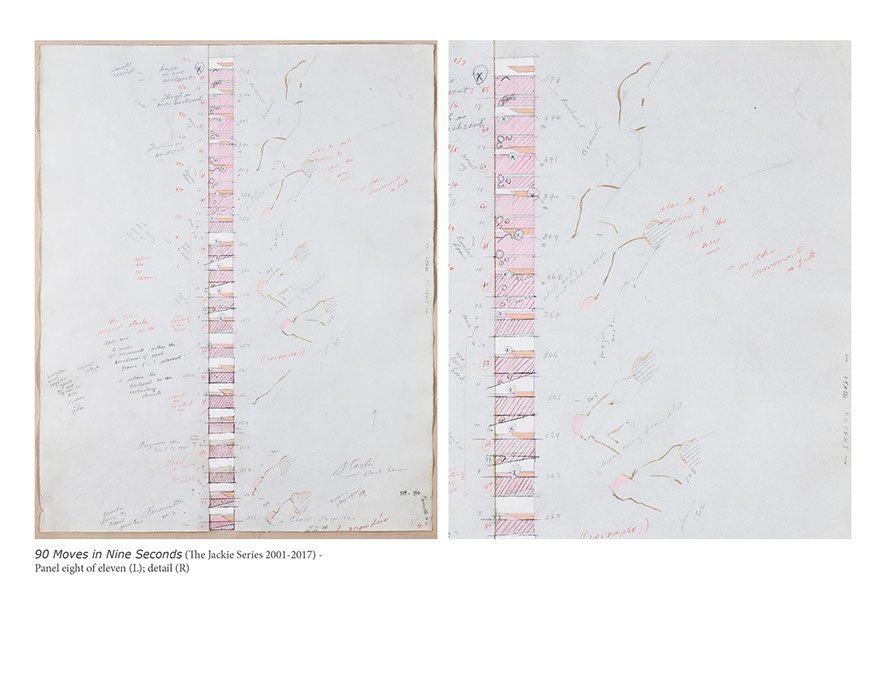

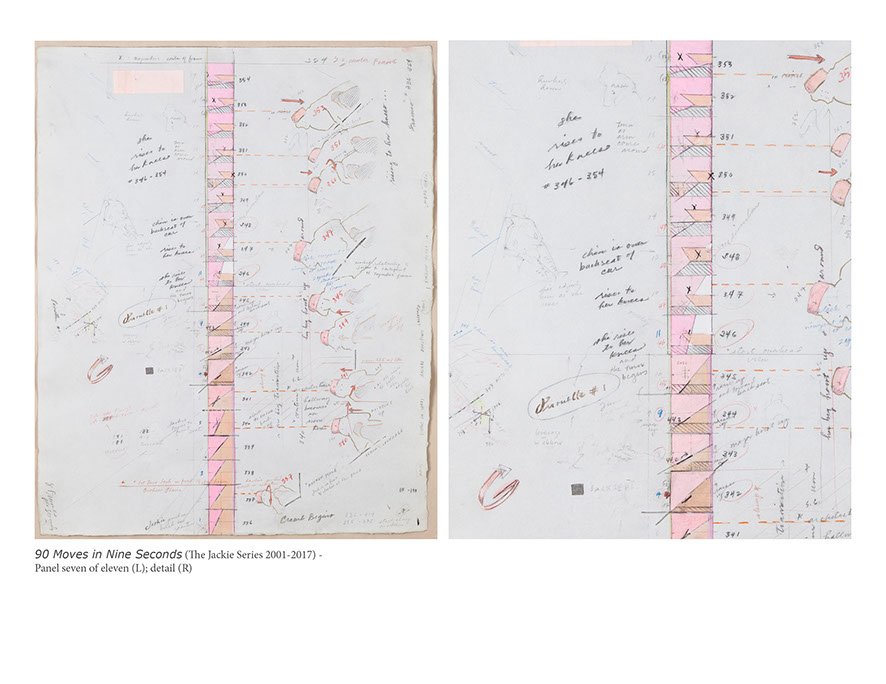

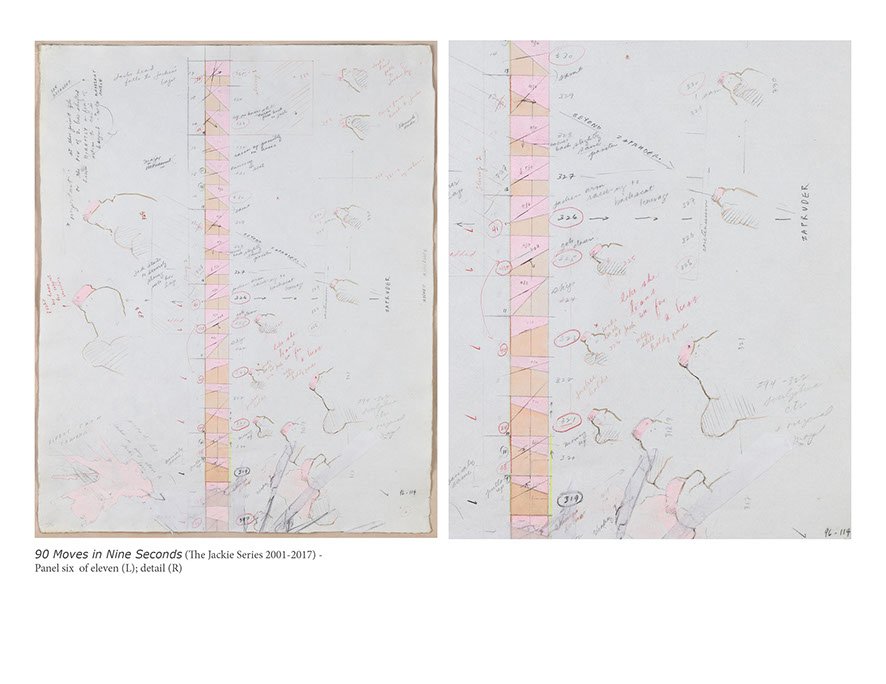

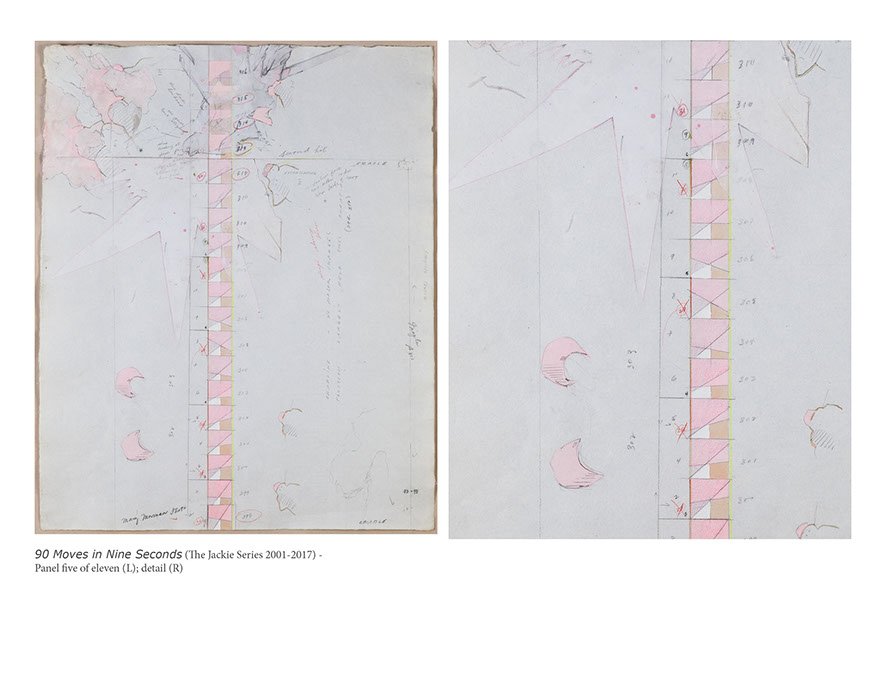

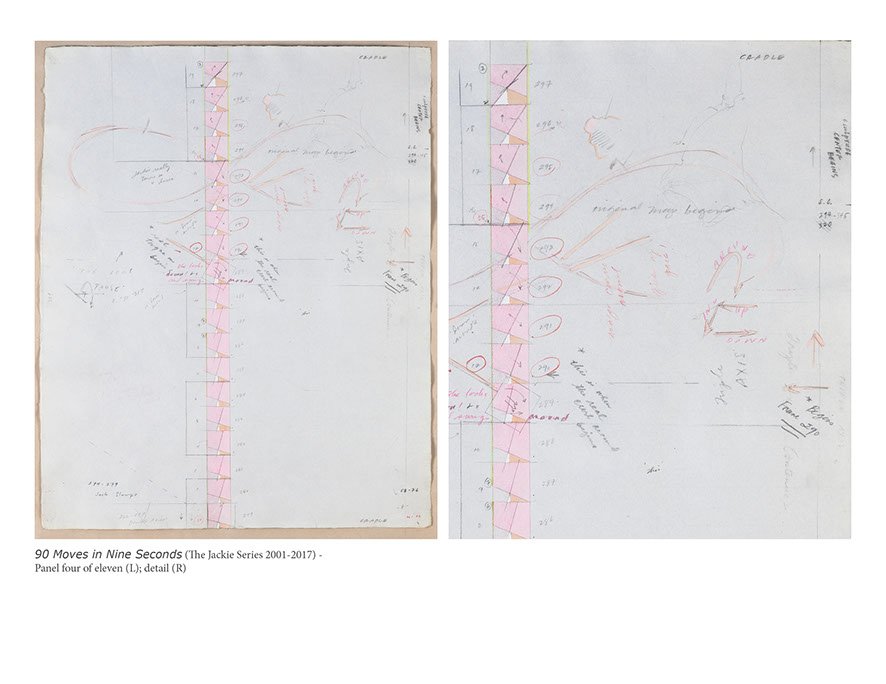

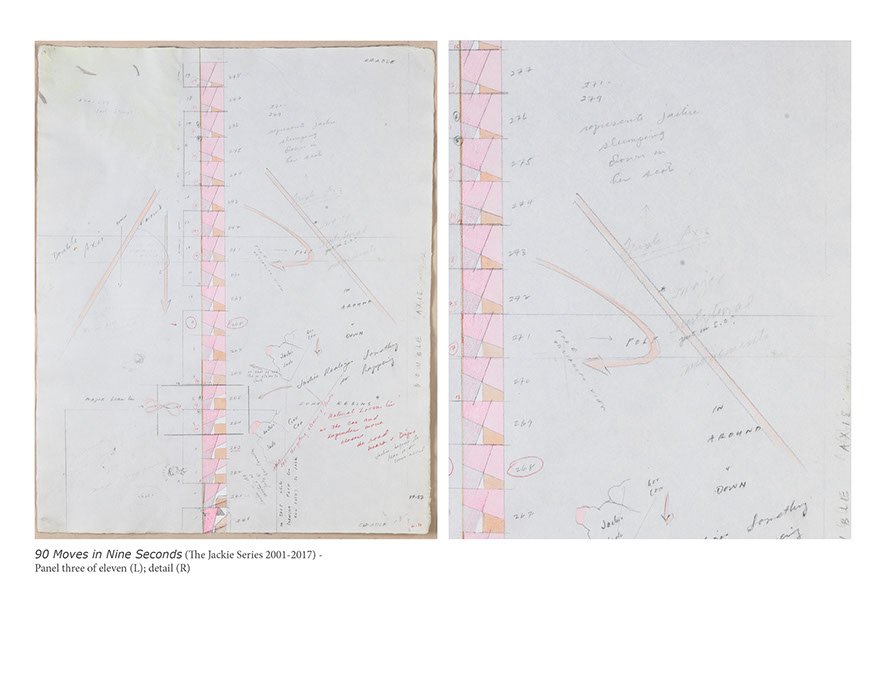

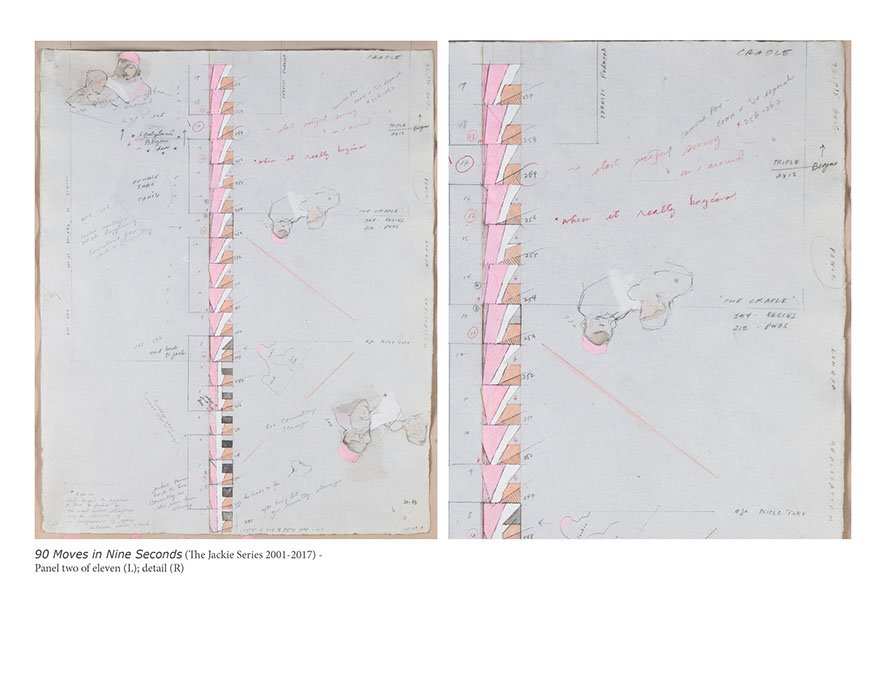

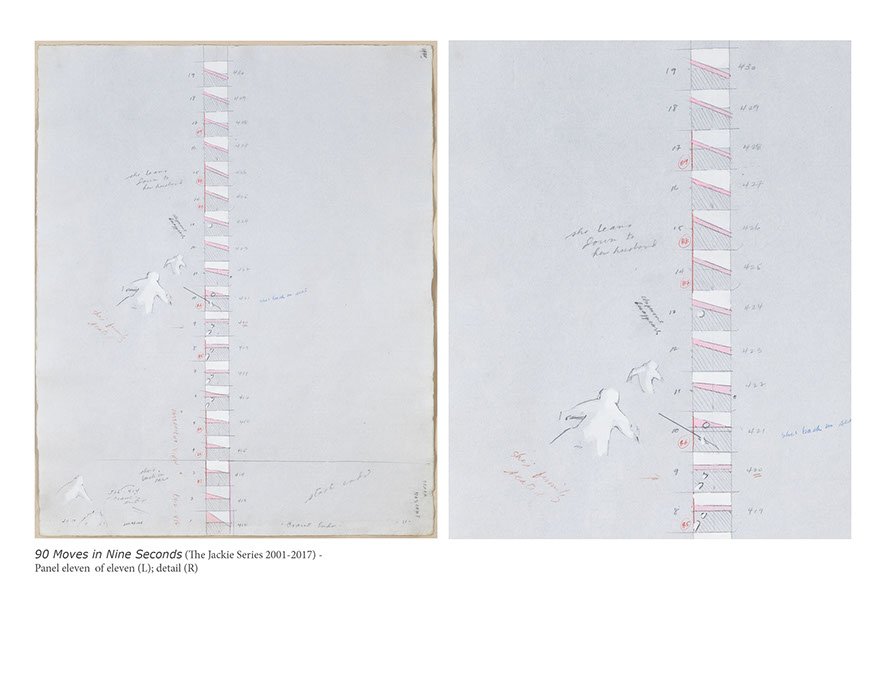

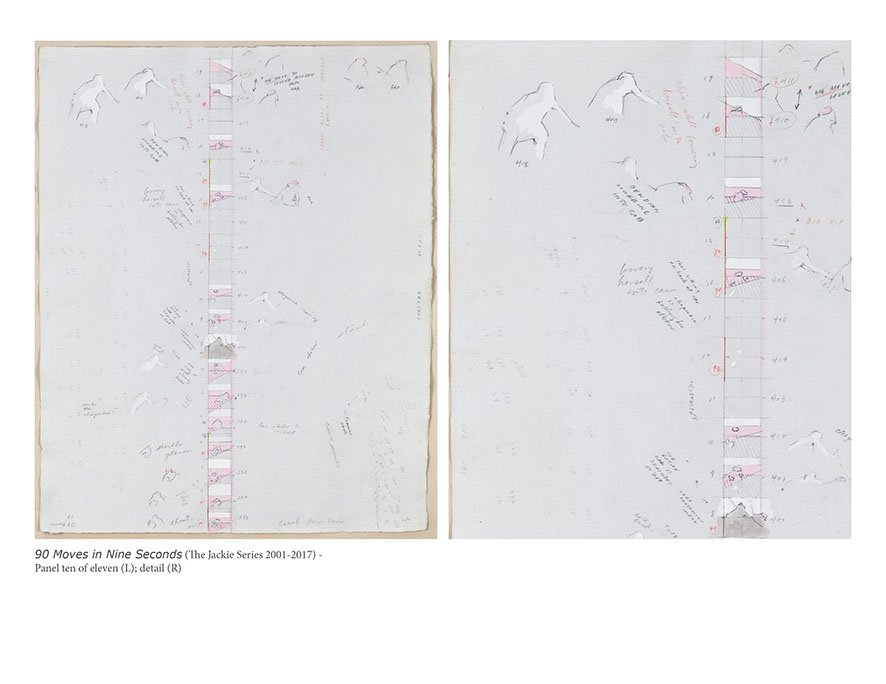

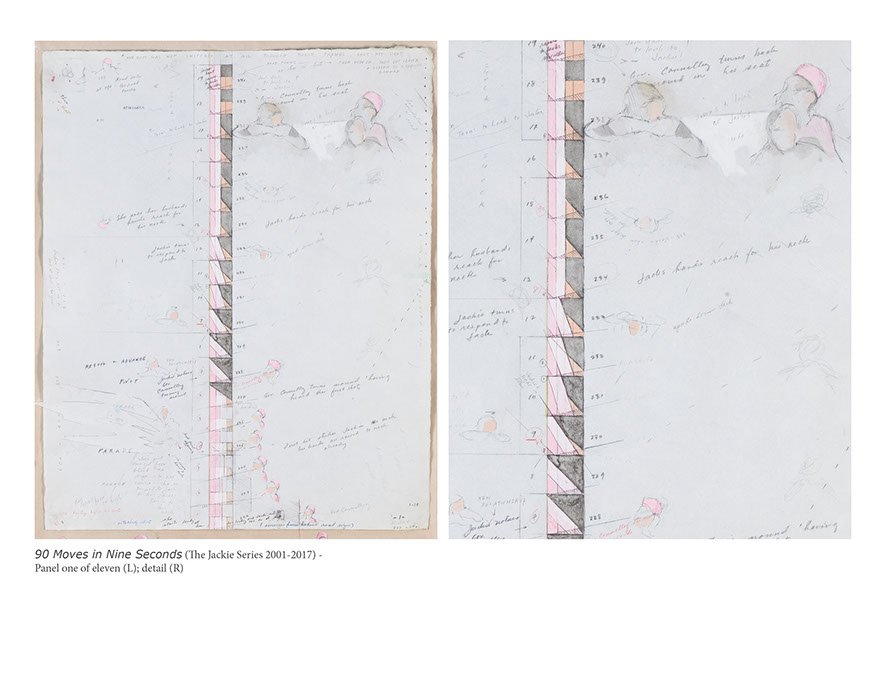

The work 90 Moves in Nine Seconds (The Jackie Series 2001-2017) by the New York-based artist Jen Durbin reconstructs the Dallas event, focusing on the original Zapruder footage. The work consists of an 11-part installation made of wood, reed, plaster, paper maché, and felted mohair, exhibited with an 11-panel drawing, models, and maps. At the center of her almost forensic exploration is the movement Jackie´s pink hat makes after the shooting. Spending 16 years in recreating the trajectory, Jen devised 11 diagrammatic drawings organized around the images Zapruder caught on film. These drawings can be seen as sketches for the installation exhibited in 2017 at “Art 3” in Brooklyn, but after taking a closer look, I realized that they could also be studied as an autonomous work. Hence, instead of focusing on the installation, I will try to unravel the puzzle of the drawings, asking under what circumstances could they be interpreted as tools for sharpening our political imagination.

Suppose official (but also alternative) histories in the case of the JFK assassination always depart from the bullet. In that case, Jen´s choice to spin her concept around the iconic hat can already be interpreted as a political decision that challenges the masculinist narratives (the bullet being a clear signifier of the phallus). Organizing her drawings around the vertical space of the frames, she thus highlights the supremacy of phallocentric trajectories. These images reveal the dominant hierarchical orientation of space/time at the graphical level, which becomes a sign of entrenched subordination and gender violence. Yet, it is precisely the insistence on the vertical columns in the drawings that opens up the gaze for the moment when Jackie lifts herself into the air after the shooting. In other words, the choreography of 90 Moves in Nine Seconds translated from the medium of film into the materiality of drawing is an attempt to reclaim verticality, turning it into an aesthetic space of emancipation, a deconstruction of signs of patriarchal subordination. This, I would say, is the first argument for the drawings having an immanent political dimension.

Let´s now take a closer look at the figures and the narrative constellations embedded in the work. Besides the repeated motif of the pink hat, the images consist of handwritten text, numbers, and arrows. More than an accumulation of optical shapes and figures, the graphic elements establish various constellations with words, creating a multi-layered pictorial plane without clear-cut borders between visual and verbal signs. In that sense, my first association regarding Jen´s drawing was that they expose a diagrammatic space where the focus is not on the representation of objects, things, persons, or events but forms outlined in their transformation and becoming. Interpreting diagrams as “a kind of intertwining,” “an ambiguous, indefinite relation of subject-world intertwining,” philosopher John Mullarkey concludes that diagrammatic thinking is a spatialization of thoughts, aiming to embody real and actual connections. (Mularkey 2006: 159) As a recreation of the vertiginous movement that has shaped history, the drawings capture the perplexing moments of chaos, violence, and fear, all of which are privileged signifiers of the aesthetic regime of contemporary politics.

The focus on syncopated time and the stills translated from Zapruder's film resembles the stop-motion tests practiced by Eadweard Muybridge, an English photographer at the turn of the 19th century, considered a significant figure in the development of cinema and the art of moving images. Muybridge became known for experiments called “Bullet time,” a visual effect of time and space being decelerated down with the help of technical apparatuses. Similarly, the drawings slow down our perception, emphasizing the kinetics of a body being exposed to shock and panic. If the capitalist machine operates within the parameters of high velocity and restless motion, then – in opposition to the hectic temporality of deregulated circulation – 90 Moves in Nine Seconds introduces another kind of temporality, one oriented towards accumulating absences and caesura. Regarding the idea of absence, the following must be noted: while the bullet, the rifle, and the assassin's pistol are well preserved and secured in the National Archives, the whereabouts of Jackie´s pink pillbox hat are unknown. Retrieving the missing object and bringing it back to our consciousness, Jen (re)acts against amnesia, activating a counter-memory, which is a political action per se, as it reveals invisible/omitted chapters of history.

Carefully reconstructing the position of Jackie´s body in relation to the President, the drawings map the changing direction of her gaze and address the act of looking and witnessing. In the context of numerous conspiracy theories, such an undertaking aiming at historical accuracy shows how important it is to insist on truthfulness. Yet, what the drawings paradoxically disclose, is precisely the unstable and shifting position of the witness. The movement of the pink hat corresponds to the equally disordered pattern of historical time, compressed in the 486 frames and reassessed in the 11 drawings. Being more than just an aesthetic reflection on the murder of JFK, the drawings confront our understanding of knowledge and, in so doing, become performative epistemic documents about loss, the invisible, the irresistible violence of politics, and the fragile border between fiction and documentation.

In the concluding paragraph of the chapter “Death, Sex, Love of the Invisible” (from the book The Pleasure in Drawing), the French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy writes: “The fever of drawing, the fever of art in general, is born of the frenzied desire to push form right to the limit, to make contact with the formless, as an erotic fever pushes bodies to the limits of their own forms.” (Nancy 2002: 78) For Nancy, pleasure in drawing is ambiguous because it cannot be reduced to positivity and is not straightforward: instead, it comes into being with the tension between the desire of the self and the outside, which is the region of the non-self. Finally, this dialectic triggers the philosopher to formulate an ethics of pleasure which reads as ethics of drawing: “Nothing moral, then, but rather what might well be called an ethics of pleasure: a pleasure that does not let itself be satisfied, that refuses satiety, and whose exigency never fails to turn into sorrow.” (Nancy 2002: 78)

Looking at Jen´s drawings as I was writing the text, it seemed that the ethics of drawing Nancy writes about signifies a possible conceptual departure point for claiming that 90 Moves in Nine Seconds inaugurate a specific political imaginary. Yet, I want to insist that the politics here is not reducible to the mere content of the work, but rather, it concerns the form and foremost the materiality. In contrast to the omnipresence of digital images, these drawings foreground a paradoxical sense of the physical body that is losing ground. It is also an affective recording of a gesture that keeps hovering between the fixed time of the past and an anticipation of the form that can be sensed in its immediate presence. Thus, the drawings become political in their potentiality to reorganize the relationship between what is visible and what escapes visibility and remains hidden and unseen (like the “real” pink hat). Their diagrammatic force intertwining cartographical, numerical, filmic, and textual traces restages politics as an antagonistic event of chaotic forces. In doing so, they invite us to become witnesses of absences and invest desire to retrace lost utopias of a different history and start imagining less violent futures.

Jen Durbin is a sculptor based in New York City.

Originally from Springfield, Illinois, she attributes her interest in fine art (despite hailing from a small town without it) as much to the intimate proximity of a walk thru Abe Lincoln’s home, as to the sequential nature of the Stations of the Cross.

Durbin’s forms utilize the inherent bond between sculpture and the moving image to bring to light the viewing experience as a living space. Centered around iconic moments in the psychic and/or historical memory, her work is often pointedly American. These figureless forms and uncanny familiars linger at the periphery of our shared story, and time and again expose the female figure rendered invisible.

Her large-scale assemblages, comprised of humble materials and commonplace objects, meticulously map the mediated moments that linger and stay. Durbin’s sculptures are both kinetic and combusting, offering a haunting glimpse of an attunement to that which we erase. By uncovering these forgotten frames, she is navigating territory beyond the visible - insisting that when objects cohabitate with memory, they take up an enduring space.

After completing a degree in Journalism and Literature at UW-Madison, Jen Durbin received her BFA from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2000, and her MFA from Yale in 2003. Durbin has exhibited in the US and abroad including shows in Chicago at Arena Gallery, Contemporary Art Workshop, Gallery 2/SAIC and The Law Office; installations at NEWD Art Fair in Brooklyn, New York; as well as solo shows with Motus Fort Gallery in Tokyo, Japan - Capsule Gallery and Silas Von Morrisse in NY.

Her acclaimed show 90 Moves in 9 Seconds (Art Forum, Best of 2017) documents the movements of Jackie Kennedy’s infamous pink hat as she reacts to the unfolding tragedy. A series Durbin mapped over a nearly 20 year span.